Asteroid Mining Race: AstroForge's Odin Mission and the $10 Quintillion Resource Rush

February 2025 marked a pivotal moment in commercial space exploration as AstroForge’s Odin probe lifted off aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, tasked with scouting asteroid 2022 OB5—a near-Earth M-type object believed to hold platinum-group metals (PGMs) in quantities exceeding all terrestrial reserves combined. By early March, however, the mission hit a critical snag: ground control teams lost contact with the 120-kilogram spacecraft, despite repeated attempts to re-establish communication via NASA’s Deep Space Network. In a March 12 statement, the California-based startup confirmed that the likelihood of recovering the probe was “extremely low,” framing the loss as a costly but invaluable learning experience in the high-stakes race to unlock space resources valued at ten quintillion United States dollars.

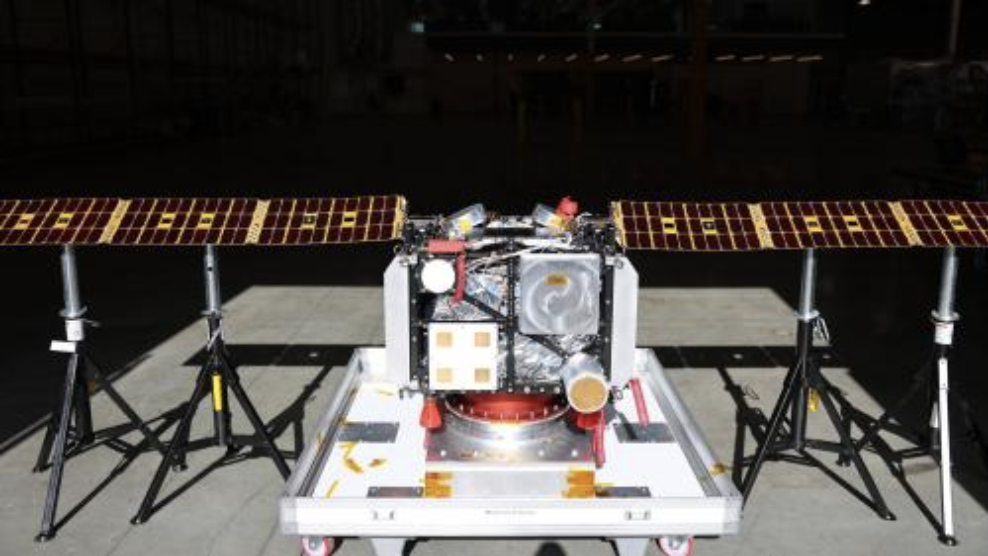

Odin’s core objective had been to map 2022 OB5’s surface composition and gravitational field, data critical for AstroForge’s follow-up Vestri mission (slated for 2026), which aims to land on an asteroid and demonstrate in-space resource extraction. Built in just nine months for three point five million United States dollars, the probe embodied the “agile innovation” ethos of commercial space—prioritizing rapid prototyping over perfect execution. Engineers suspect the loss of contact stemmed from a failed solar panel deployment: Odin relied on a compact, foldable panel design to fit within the Falcon 9’s payload fairing, but telemetry data in the final transmission suggested one panel failed to lock into place, cutting power to its communication systems. Even so, the mission’s modular architecture—with separate pods for navigation, imaging, and power—offers a blueprint for future probes, as teams can isolate and refine problematic components without overhauling the entire spacecraft.

The setback has not slowed the broader asteroid mining industry, which is projected to grow at a 19 percent annual rate through 2031, reaching six point three billion United States dollars in market value. Competitors are advancing diverse technical paths: Bradford Space recently tested a water-based thruster system in low Earth orbit, enabling precise maneuvering near asteroids—critical for avoiding collisions during landing. Ispace, fresh off a 2024 lunar lander test, is developing AI-powered hexapod robots that can traverse uneven asteroid terrain, while Karman+ secured two million United States dollars in seed funding to focus on extracting water ice from carbonaceous asteroids. Water, in particular, stands as a top-priority objective: it can be broken down into hydrogen and oxygen to serve as rocket fuel—a capability that could potentially drastically reduce the cost of deep-space missions by doing away with the requirement to launch fuel from Earth.

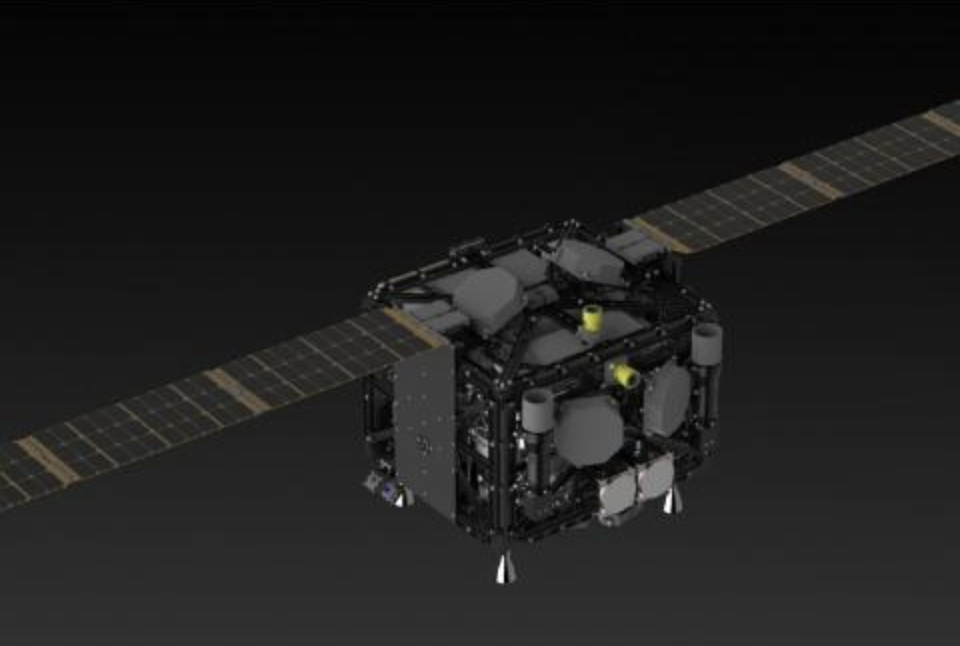

AstroForge itself is doubling down on the 2026 Vestri mission, incorporating lessons from Odin. The next probe will feature a redundant power system—with two independent solar arrays—and a backup communication antenna linked to a dedicated battery reserve. It will also use Safran’s EPS®X00 electric propulsion system, which delivers 1.7 kilowatts of power (nearly ten times Odin’s capacity) and a 5,000-hour thruster lifespan, reducing the risk of propulsion-related failures. These upgrades reflect the industry’s ability to iterate quickly: while government space missions often take a decade or more to develop, commercial ventures like AstroForge can adapt designs in months, driven by the urgency to tap into asteroid resources that could reshape Earth’s economy.

Legal and ethical questions persist alongside technical progress. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty prohibits nations from claiming celestial bodies, but it does not explicitly address who owns resources extracted from them. In 2025, the United Nations held a series of working groups to draft a framework for space resource governance, with participants including the United States, Japan, and the European Union. The United States has already passed legislation allowing companies to own and sell space-mined resources, creating a favorable regulatory environment for startups, while the EU is considering similar rules. Dr. Chris Lewicki, a former NASA engineer and space resource expert, notes: “We can’t have a gold rush without rules—clear governance will prevent conflict and ensure benefits are shared globally.”

For AstroForge and its peers, Odin’s loss of contact is not a defeat but a milestone. As CEO Matt Gialich told reporters in March: “Every failure teaches us more than a hundred successful tests.” With Vestri in development and competitors advancing parallel projects, 2025 remains a defining year for asteroid mining—a sector that promises to turn cosmic abundance into a solution for Earth’s dwindling critical mineral supplies. The ten quintillion United States dollar resource potential is no longer a distant dream; it is a target that drives innovation, collaboration, and resilience in the quest to make space humanity’s next economic frontier.

(Writer:Lily)